Christopher Isherwood by David Michon

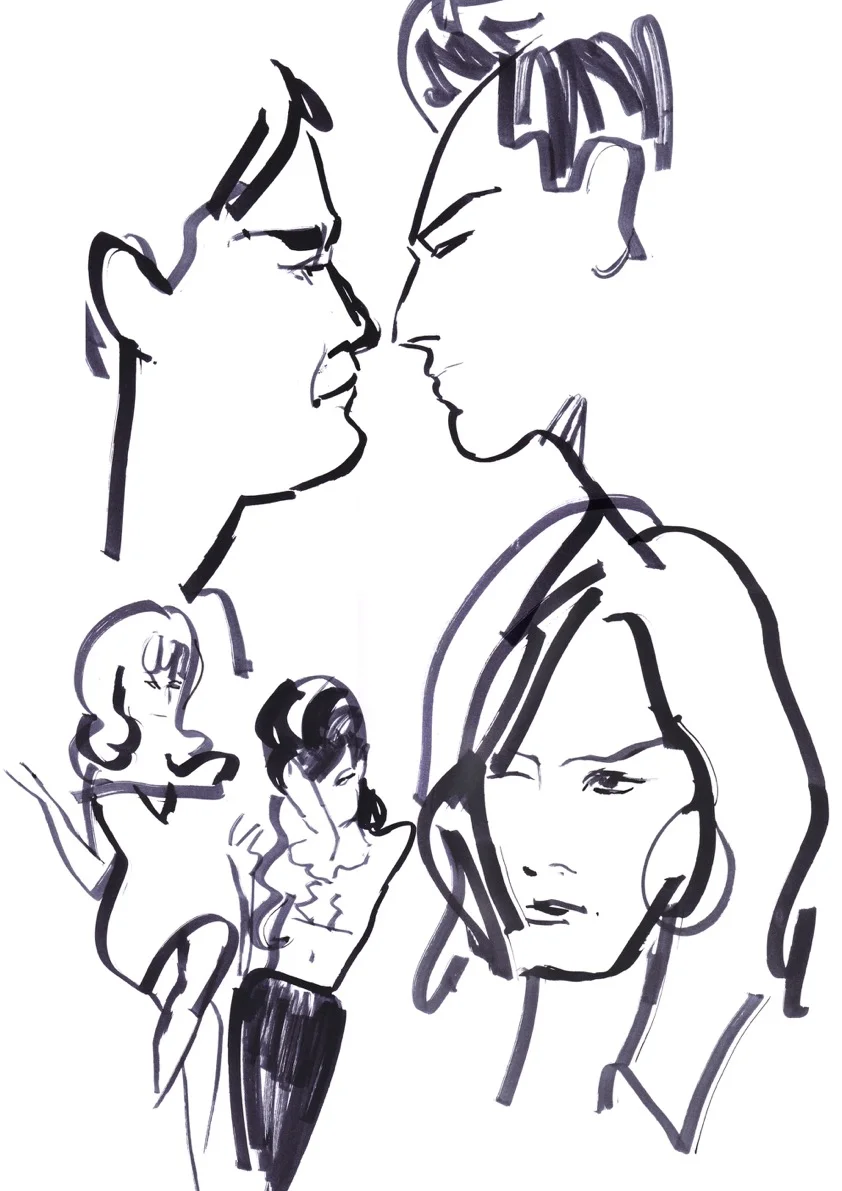

Illustration by Sam Russell Walker

David Michon is a journalist, producer and strategist. He's worked for Monocle and Icon magazines, Winkreative creative agency, and now freelances, with clients that include esteemed print publications, progressive developers, non-profits, award-winning design firms, and even a Buddhist monastery. Originally from Winnipeg, David has lived in London since 2009.

Christopher Isherwood: novelist, memoirist, and dramatist. But also: hero to the left and to gays, pacifist, fiercely loyal friend and lover. He is famous for his fiction, with his stirring narratives of encounters between banality and extremity, which make up some of the 20th century’s best literature. Yet, his work was a reflection of what was happening in his own remarkable – and at times remarkably ordinary – life.

Like many others, of the less literary sort at least, my path first crossed Christopher Isherwood’s via the screen, thanks to Cabaret – Liza Minnelli’s Oscar-winning tour de force, and an adaptation of Isherwood’s 1939 book, Goodbye to Berlin. The story of a loose and ambitious, nightclub-performing American woman in 1930s Berlin, and the naïve young British man, just moved to town, who ends up taking a room in the same house.

Liza Minnelli in Cabaret by Sam Russell Walker

Expertly, it portrays a city that is at once a perfect and intoxicating bohemian fantasy, and also the crucible of a political force for which that fantasyland is a primary target. The story exists at the precipice of salvation and certain ruin.

Isherwood was, for 90% of his career, his own protagonist; he was the William Bradshaw (his middle names) in Mr Norris Changes Trains, a young English writer arriving to an unravelling Weimar Berlin (which he did in 1929). In Goodbye to Berlin, this parallel was made almost confusingly obvious, as “Christopher Isherwood”, the character, took to the page.

Striking in Cabaret was to see a bisexual main character that is not just a catch-phrase cliché, a camp comic relief, or who is in some way punished particularly for his sexuality. There are few other examples of such a story that have hit the mainstream and won anything near an Oscar for it.

Yet, for someone whose writings, it is said, were tantamount to “dispatches from the gay front” (The New Yorker), he struggled with homosexuality in his earlier work, as you might expect. In the novel, William Bradshaw, despite being an Isherwood stand-in to a large extent, is straight. Would it have been, in 1939, a distraction in Goodbye for its lead to be an open homosexual or bisexual? Probably.

Thankfully, in 1964, Isherwood gave us A Single Man – again which was adapted into successful film, likely bringing a new generation audience into the Isher-world via the movie theatre. Still, A Single Man isn’t about homosexuality – it’s about love and loss, lust, aging, mental health. The story, as Isherwood tells it, has immense grit, more than the film’s director Tom Ford let seep into his hermetically sealed mid-century style fantasy. And, just as in Goodbye, gayness wasn’t the reason A Single Man was a story worth telling. (Something still completely refreshing in the realm of gay storytelling.) In the former, it had to be left out to keep our attention where it was meant to be; in the latter, 25 years on, Isherwood perhaps believed we’d come far enough to see beyond it.

Colin Firth in A Single Man by Sam Russell Walker

As a writer, Isherwood’s biggest shortcoming is also what makes his work so fantastic to read – he really isn’t particularly imaginative. He wrote about his surroundings, his fantastical friends, thinly-veiled (the sexually liberal Jean Ross as Sally Bowles; the dubious charmer Gerald Hamilton as Mr Norris), and so when we encounter homosexuality, for instance, it’s because that is his world, not as some imported plot point.

Born to a venerable British family, Isherwood didn’t feel as if he fit in – he despised the middle classes, and in particular felt uncomfortable having sex with middle class boys (though he apparently often slept with his close friend W. H. Auden). He took off to Berlin, after getting himself kicked out of Cambridge University, to find some foreign working class boys to sleep with, as if straight out of Pulp’s Common People. He’s famously written that, to him, Berlin meant boys. Amen.

More than that, though – i.e. beyond sexual and class tourism – he was in search of a place where he felt at home. The world of his prudish, rich mother Kathleen wasn’t his – it was part of the world of the “Nearly Everybody”: polite, ordered, and laden with responsibility. “Damn Nearly Everybody,” he writes. A sentiment most of those profiled on Queer Bible likely share. So, Amen, again.

He makes mention of the interesting moment in gay history in which he lived in his autobiography, Christopher and His Kind. In 1934, his then-boyfriend Heinz Neddermeyer was refused entry to the UK, where Isherwood was working for the film director Berthold Viertel. By all accounts, it was partially because Heinz was thought to be gay. Viertel, in the days after, made some quite banal gay joke to Isherwood (not knowing his persuasion), in response to which Isherwood wrote in Christopher and His Kind: “Homosexual lust they could laugh at, now, and tolerate in a sophisticated way. Homosexual love they put to death by denial.” We feel only just barely past this point now.

Emigrating from Berlin to Hollywood in 1939, Isherwood eventually settled in Santa Monica until his death in 1986, finding lasting love in Don Bachardy – who was 30 years his junior, and became a moderately good portrait artist. He also found a new quest in life, becoming a devotee to Hindu philosophy. He once said he liked California for its ever-present sense of mirage, the buildings of Europe being somewhat too “solid”; his happy place maybe finally found in one that didn’t feel like so much of a place at all.

When you watch interviews of Isherwood, later in his life, he has such an indelible youthfulness. Bright, wide eyes; mischievous smile. Never the Nearly Everybody, but likewise never trying to be anything more than himself. He says, of happiness: “In some cases, happiness has consisted of intense excitement, even danger, discomfort. Other times, happiness has been just lying on the beach, or lying in bed watching television. Then again, of course, there’s the happiness of following your ideas, thinking, after all, that sentence really is alright.”

Back in the 1920s, after a trip to Amsterdam with Isherwood, Auden wrote in a guestbook a quote from another poet: “Read about us and marvel! You did not live in our time—be sorry!” And though Isherwood comes to mock those lines, they seem right on the money.

Sam Russell Walker is an Illustrator based in Glasgow. He graduated from the Glasgow School of Art in 2015 and his work is inspired by film, pop culture, the human form, plants and fashion. His process is also heavily influenced by the act of mark making and creating textures through this process.