Tove Jansson by Rosalind Jana

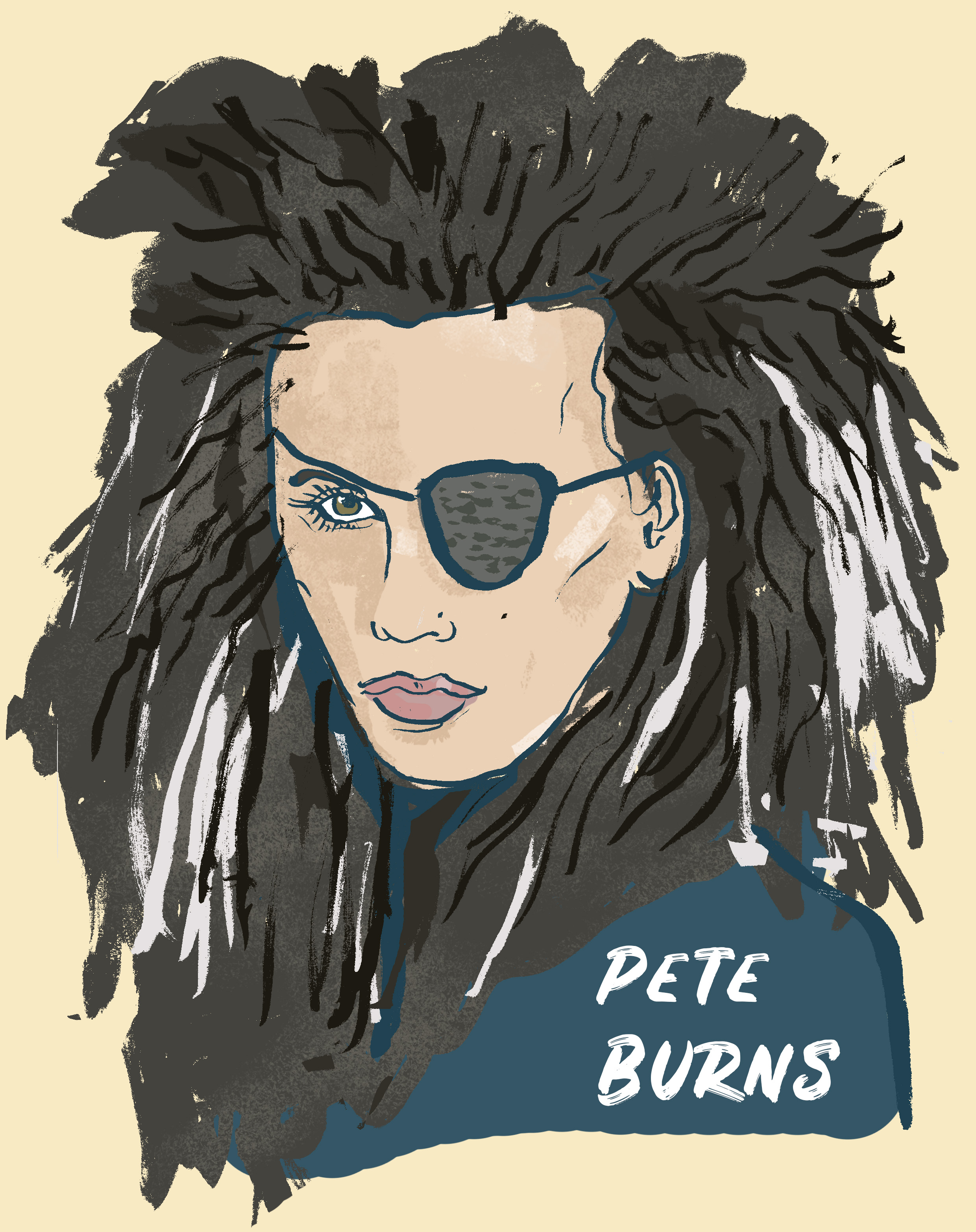

Illustration by Louise Pomeroy.

Rosalind Jana is an author, journalist and poet. She has written for places including British Vogue, Buzzfeed, Dazed, BBC Radio 4, Refinery29, Broadly and Suitcase, and is currently Violet magazine's junior editor. Her debut non-fiction book 'Notes on Being Teenage' came out with Hachette (Wayland) in 2016. Her poetry collection 'Branch and Vein' is available through the New River Press.

Tove Jansson by Louise Pomeroy.

Picture it. A woman with grey hair and a grin wide as the sky. She’s swimming – jaunty flower crown angled perfectly on her head, the whites and yellows bright against the blue sea. Behind her, back on land, there’s a hut. It’s small and grey and sturdy. In the very corner of the frame another woman is scrambling over the rocks. One more step and she’d have been out of shot.

Maybe you don’t need to picture it. Maybe you’ve already seen the image: retweeted onto your timeline, or posted on Instagram, or found on some other corner of the internet where it frequently does the rounds. No wonder. It’s a photo that epitomizes everything that’s right about salt water and sunshine and floral headgear. It looks like bliss.

The woman in the photo is Tove Jansson: Finnish author and artist, best known as the creator of the massively successful Moomins series (and subsequent franchise stretching from a TV to opera to collectable figures to anything that could be emblazoned with a soft, snout-nosed creature). The setting is Klovharu: the tiny island she owned with her partner Tuuliki Pietilä, in the Pellinki archipelago. The two of them spent almost thirty summers there.

I’ve had this photo in a folder on my desktop for the last year or two. It’s the kind of image I occasionally pull up on a grey day when I need a reminder of what full-bodied joy looks like.

I’ve adored Tove Jansson for a long time. Like plenty of kids, I spent hours in the company of Little My, Snufkin, Snork Maiden, and the whole Moomin clan. As a teenager recovering from spinal surgery, I was drawn back to that world of valleys, storms, theatrical antics, proprietary Hemulens and perfect stretches of sea, finding it deeply comforting when so much was beyond control.

Recently, I returned again. This time it was different. In the interim I’d saved that photo of Tove-with-flowers to my desktop. And avidly read plenty about her. Now I could rattle off biographical details about her sculptor father and illustrator mother; about her her time spent studying in Sweden and Paris; about the fact that, alongside the Moomins, she was also an accomplished painter, thinker, stridently anti-fascist political cartoonist, and writer of spare, beautiful prose for adults.

I could also talk at length about her lesbian relationships.

See, in that same interim I’d also gone from unquestioningly assuming I was straight to realizing that much as I continued to be attracted to men, I also really fancied women. The realization happened in stages; taking time between the articulation of this pretty simple fact to myself, and acting on it.

In the meantime, I found myself nudged along the way by a number of figures – Tove Jansson, Frida Kahlo and Virginia Woolf among them – who I’d gravitated towards anew almost without registering just why I was suddenly, weirdly keen to glean every scrap and detail of their personal lives. The relationships they had with both men and women (not to mention their creativity, ambition and often superlative outfits) meant they soon became an unofficial set of beacons; each a kind of glittering promise that - for me at least - life, sex, love, desire, and emotional terrain could be even richer for being queerer.

Tove was high up that list. Of course she was. A multitalented, astute, restless woman who also knew the power of a good pair of tartan trousers; who also happened to be a really bloody good writer. With her own island. What more could I want in the way of encouragement?

Perhaps she also stuck out because of her books. Here was a childhood reference point revisited - and a set of resonances to appreciate anew.

See, Tove often wove her life into her fiction, refiguring the people she loved as remarkable characters. First, there was her affair with theatre director Vivica Bandler – the first time she’d fallen for a woman (an experience described in a letter to a friend as “one big state of joy and torment”). As well as painting Vivica into a mural in the Helsinki City Hall, Tove inserted an inseparable pair of creatures - Thingumy and Bob - into her third Moomin book The Magician’s Hat. The pair communicate with each other in a secret, almost impenetrable language, and carry a suitcase with them, its contents (a giant, very precious ruby) kept for their eyes only. In a country where homosexuality remained illegal until 1971 it’s not a hard metaphor to unravel.

In 1955 Tove then met Tuulikki – also an artist - at a Christmas party. She invited her to dance. Tuulikki turned her down, but the encounter led to a relationship that lasted until Tove’s death in 2001. Tooti, as Tove nicknamed her, appeared in the guise of Too-Ticky in Moominland Midwinter: a pragmatic, sturdy character who offers Moomintroll a dash of much-needed resilience. Too-Ticky’s unflappability is a revelation; as is her clear-sighted assessment that “everything is very uncertain, and that’s what makes me calm.”

Many other aspects of their relationship – not least the trials of combining companionship with creative drive – also make their way into her later novels and short stories including Art in Nature and Fair Play. Here her writing is compact, laced with wry humor and a wonderful eye for the idiosyncratic details of love, travel, work, and cohabitation.

In that desktop folder I’ve got plenty of other photos of Tove, from cool youth to jubilant-looking old age: her standing in her studio, terribly glamorous with hands in pockets; painting a mural, clad in a striped shirt and wide-legged trousers; perched on the water’s edge, sturdily practical in jeans and a thick-knit jumper; in a zesty orange coat, surrounded by artworks; every bit the bombshell in a swimsuit atop a pile of rocks, one arm flung above her head. There’s a vitality to all of them. They look like images of a life well lived.

What I love best though are the snaps of her and Tuulikki: on their island, all rocks and endless ocean; both smiling in cowboy-style outfits; working together on their boat as Tove proffers a net full of fish to the camera, Tuulikki on the oars behind. There is something so everyday, and so achingly gorgeous, in them.

This idea of their life built together - one that was steadfast, creative, practical and full of pleasure, as well as its fair share of friction - still appeals deeply. I might not have been consciously seeking it on those initial tumbles through Google images, but their partnership absolutely offered up room to think about alternative futures for myself. Ones that were less limited, that somehow felt like a relief in their plurality. Ones that continue to be exhilarating. Ones I’m now deeply, wildly glad to be able to imagine (proximity to sea always an optional added extra…)

Louise Pomeroy is an illustrator from Brighton, currently based in London. Her work is a mix of hand-drawn line and digital colour. She especially enjoys drawing portraits, hair, plastic bags and fetish imagery. Find her at www.louisezpomeroy.com. Follow her in on Instagram.